15 mujeres surrealistas más importantes

- OCA | News

- 28 jun 2024

- 37 Min. de lectura

OCA|News / ArtNews / / Junio 27, 2024 / Internacional / Fuente externa

POR KAREN CHERNICK / ArteNews

Los surrealistas franceses fundadores amaban el subconsciente. También amaban a las mujeres, como musas, como sujetos de deseo erótico, como fuentes de inspiración, pero no necesariamente como artistas al principio. Las mujeres no estuvieron presentes en el nacimiento del movimiento cuando el poeta André Breton publicó su Manifiesto Surrealista en 1924. Pero inevitablemente las mujeres se sintieron atraídas por el movimiento y sus ideas revolucionarias: interpretan los sueños como expresiones del pensamiento subconsciente, fusionaron lo familiar con lo desconocido, y, en general, eliminar la inhibición racional. Algunos de ellos llegaron al surrealismo a través del contacto con surrealistas masculinos, otros llegaron por su cuenta y otros, fuera de París, lo hicieron a medida que las exposiciones internacionales ampliaron el círculo surrealista.

"Las mujeres no estuvieron presentes en el nacimiento del movimiento cuando el poeta André Breton publicó

su Manifiesto Surrealista en 1924".

Y así, apenas unos años después de que Breton definiera el Surrealismo, afirmando en terreno conceptual que se trataba de “automatismo psíquico en estado puro, mediante el cual se propone expresar –verbalmente, mediante la palabra escrita o de cualquier otra manera– el funcionamiento real del pensamiento”, las mujeres participaron activamente. Mostraron sus pinturas, fotografías, collages, ensamblajes, prendas y esculturas en exposiciones colectivas surrealistas y tuvieron sus propias exposiciones individuales, con introducciones al catálogo escritas por surrealistas de su círculo.

Entre 1924, cuando Breton publicó el primer Manifiesto Surrealista, y 1947, cuando una importante exposición en la Galerie Maeght celebró el regreso del surrealismo a París en la posguerra, la “primera generación” de surrealistas incluyó a numerosas mujeres, muchas más de las 15 incluidas aquí. Cada una tenía su propia y compleja relación con el movimiento.

“La diversidad de experiencias y actitudes por parte de las mujeres artistas activas en el surrealismo ha demostrado ser tanto un obstáculo como un desafío”, escribió la historiadora del arte Whitney Chadwick en su innovador texto de 1985 Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement. “Al final, llegué a ver esa diversidad como un tributo a estas mujeres, una afirmación de su fuerza como individuos y una señal de su compromiso con una forma de expresión creativa en la que domina la realidad personal”.

Algunos de los artistas que se describen a continuación llevaban con orgullo la etiqueta, y otros negaron enfáticamente ser surrealistas. Pero, en cierto sentido, ¿no es un rasgo surrealista por excelencia desafiar el hecho de estar metidos cuidadosamente en una caja?

Meret Oppenheim

Man Ray, Meret Oppenheim, 1932

Foto: Colección del Museo de Arte Moderno de Nueva York. Copyright de la imagen digital © The Museum of Modern Art/Con licencia de SCALA/Art Resource, Nueva York. Copyright de la obra de arte © Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), Nueva York/ADAGP, París 2024.

Meret Oppenheim tomó cosas útiles, a menudo artículos utilizados por mujeres, y con simples intervenciones las volvió completamente extrañas. En lugar de una joya, puso un anillo de oro con un terrón de azúcar blanco brillante; en My Nurse (1936-1937) ató dos zapatos de tacón alto y los colocó en una fuente de metal como si fueran aves asadas; y, lo más famoso, forró una taza de té, un platillo y una cuchara con piel en su Objeto (1936), ahora una de las esculturas surrealistas más conocidas. “El 'juego de té forrado de piel' hace concretamente real la improbabilidad más extrema y extraña”, dijo el director del museo Alfred H. Barr cuando Objeto se mostró en “Arte fantástico, dadaísmo y surrealismo”, una importante exposición de 1936-1937. en el Museo de Arte Moderno de Nueva York.

La escultura de Oppenheim demostró el hábito surrealista de desafiar la razón y permitir que surjan conexiones inconscientes e inesperadas. La artista suiza entró en el círculo surrealista tras trasladarse de Basilea a París en 1932, convirtiéndose en musa de Man Ray. En 1936 realizó su primera exposición individual, en Basilea, para la cual Max Ernst (brevemente su pareja romántica) escribió el ensayo introductorio. Su trabajo abarcó ensamblajes, pinturas y piezas de diseño (incluidos muebles y accesorios, algunos en colaboración con Elsa Schiaparelli). Aun así, no le gustaba que la encasillaran. “Nunca colaboré con los surrealistas. Siempre hice lo que quería y se podría decir que me descubrieron por casualidad”, afirmó Oppenheim en una entrevista de 1981.

Cuando estalló la Segunda Guerra Mundial, Oppenheim sintió que sus objetos eran demasiado caprichosos y pasó a la pintura, pero a menudo destruía o reelaboraba sus lienzos cada vez más abstractos. A finales de la década de 1950 había decidido poner fin a su afiliación con los surrealistas, y su último trabajo surrealista fue Spring Banquet (1959), un festín servido sobre el cuerpo de una mujer desnuda, con utensilios prohibidos, que creó primero para una fiesta en Berna y luego presentado, a petición de Breton, en la Exposición Internacional del Surréalisme de 1959 en París.

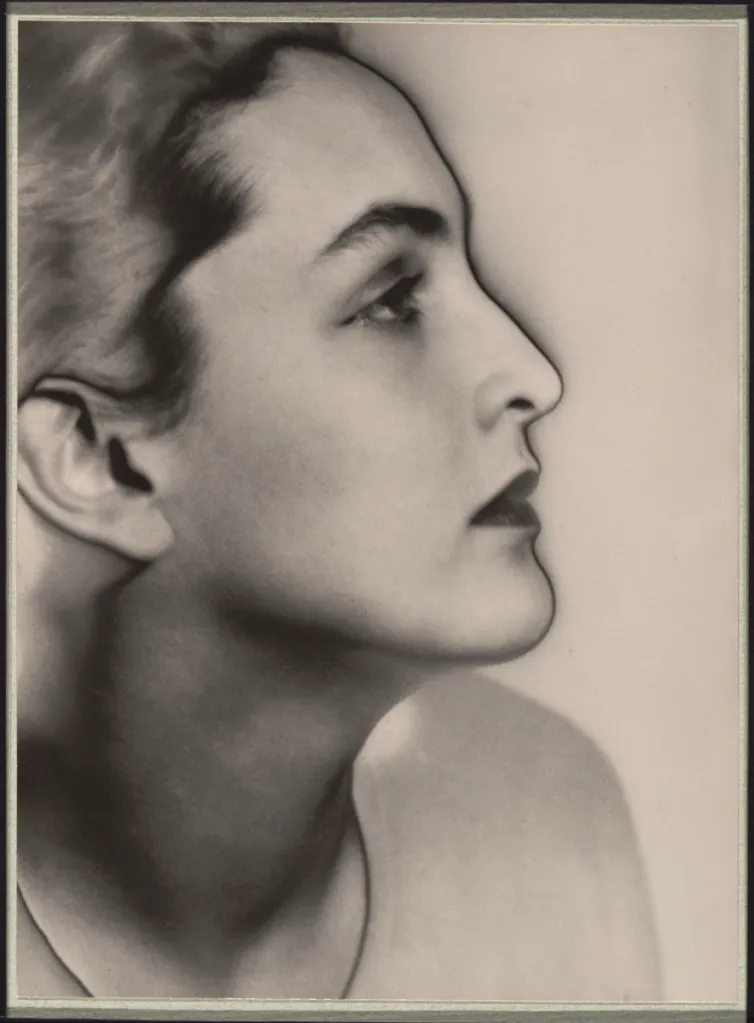

Dora Maar

Dora Maar, Autorretrato, c. 1930

Foto: Colección del Museo Nacional de Arte Moderno, Centro Georges Pompidou, París. Copyright de la imagen digital © CNAC/MNAM, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, Nueva York. Copyright de la obra de arte © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), NNueva York/ADAGP, París.

Dora Maar nunca identificó a la criatura intrigante y espantosa que aparece en una de sus fotografías más conocidas, Père Ubu (1936), que personifica su fusión de extrañeza y belleza; algunos han adivinado que se trata de un feto de armadillo. De las seis exposiciones surrealistas en las que participó Maar durante la década de 1930, Père Ubu apareció en tres (incluida la Exposición Surrealista Internacional de Londres de 1936).

Maar trabajó como fotógrafo comercial pero también se movía en círculos surrealistas. Ella y Jacqueline Lamba estudiaron juntas en la Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs de París, y Maar se hizo amiga del fotógrafo Man Ray en la época en que trabajaba con Lee Miller (quien también se convirtió en un amigo cercano). En su estudio, Maar fotografió a Meret Oppenheim y Frida Kahlo. Y ella fue la famosa amante y musa de Picasso durante casi una década.

En el estudio de fotografía que Maar abrió en 1931 con Pierre Kéfer, diseñadores como Coco Chanel, Elsa Schiaparelli y Jeanne Lanvin le encargaron crear fotografías comerciales con un toque experimental. Aportó técnicas como la doble exposición, el fotomontaje y el collage a su trabajo comercial, desdibujando la realidad y el artificio y combinando objetos de formas inesperadas. En Los años te esperan (1935), una telaraña se superpone a la imagen del rostro de una mujer en una toma probablemente creada como anuncio de una crema antienvejecimiento.

Eileen Agar

Eileen Agar, Autorretrato, s.f.

Foto: Colección privada. Copyright de la imagen digital © Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images. Copyright de la obra de arte © Estate of Eileen Agar. Todos los derechos reservados 2024/Bridgeman Images.

El collage fue una parte importante de la práctica de la artista argentino-británica Eileen Agar. Llenó su estudio con lo que llamó “fantásticas baratijas”, incluidos textiles, fósiles, huesos, conchas, hojas y muchas otras cosas que coleccionaba, y utilizó este material para crear combinaciones aleatorias de objetos curiosos. Entre ellas se encuentra Ángel de la anarquía (1936-1940), para la que utilizó una cabeza de yeso como lienzo en blanco y la adornó con pieles, plumas de avestruz, telas, conchas marinas y piedras preciosas. Aún así, era una surrealista algo reacia, que no estaba dispuesta a negar su amor por el cubismo y la abstracción para poder encajar.

Se encontró con los surrealistas por primera vez cuando se mudó brevemente a París en 1929, donde se hizo amiga de Breton y del poeta surrealista francés Paul Eluard, con quien más tarde tendría una aventura. Cuando Agar regresó a Inglaterra, conoció al pintor surrealista Paul Nash, y se embarcó en una intensa relación artística y romántica con él (a pesar de una relación continua con el escritor húngaro Joseph Bard que duraría 50 años).

Alentados por Nash, Roland Penrose y Herbert Read visitaron su estudio mientras curaban la Exposición Surrealista Internacional de 1936 en Londres, seleccionando tres pinturas al óleo y cinco objetos. “La repentina atención me tomó por sorpresa”, recordó Agar sobre la visita. “¡Un día era un artista que exploraba combinaciones muy personales de forma y contenido, y al siguiente me informaron con calma que era surrealista!” Ella rechazó la etiqueta pero expuso con ellos de todos modos, lo que permitió que Angel of Anarchy fuera incluido en exposiciones surrealistas en Londres y Ámsterdam.

Leonor Fini

Dora Maar, Retrato de Leonor Fini sentada, c. 1934

Foto: Colección del Museo Nacional de Arte Moderno, Centro Georges Pompidou, París. Copyright de la imagen digital © CNAC/MNAM, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, Nueva York. Copyright de la obra de arte © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), Nueva York/ADAGP, París.

Leonor Fini tenía que ver con la metamorfosis, la fluidez y la ambigüedad, atraída por las esfinges y otros híbridos entre humanos y animales. En La pastora de las esfinges (1941), Fini pintó criaturas sin sentido que eran mitad mujer, mitad león, pastoreadas por una amazona de gran tamaño con una espesa melena: una extraña combinación de realismo y pura fantasía.

La pintora autodidacta argentino-italiana utilizó su propio cuerpo como laboratorio de expresión creativa, vistiéndose de maneras fantásticas y usando ropas o máscaras rasgadas intencionalmente. (Sus amigas Dora Maar y Lee Miller la fotografiaron con estos trajes para la posteridad). Ella no quería particularmente convertirse en una surrealista con tarjeta, a pesar de que su enfoque resonaba con el interés de los surrealistas por descubrir correspondencias ocultas entre las cosas.

Fue Breton quien la alejó del surrealismo. "Odiaba sus actitudes antihomosexuales y también su misoginia", dijo Fini, abiertamente bisexual, en una entrevista de 1994. “Parecía que se esperaba que las mujeres guardaran silencio, pero yo sentía que yo era tan buena como los hombres”. Aún así, conoció a muchos surrealistas después de mudarse de Italia a París en 1931 y participó en importantes exposiciones surrealistas. Después de su primera exposición individual en 1932 en la Galerie Bonjean (entonces dirigida por Christian Dior), contribuyó con su trabajo a “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism” en el MoMA en1936. Ese mismo año, también comenzó a exponer con el galerista neoyorquino y campeón surrealista Julien Levy. Justo antes de que estallara la Segunda Guerra Mundial, Fini fue curadora de una exposición de muebles surrealistas para una galería parisina propiedad de su amigo Leo Castelli, y Peggy Guggenheim la incluyó en “31 mujeres” en su galería Art of This Century de Nueva York en 1943.

Dorotea Bronceado

Man Ray, Dorothea Tanning, 1942

Foto: Imagen digital Telimage, París. Copyright de la obra de arte © Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), Nueva York/ADAGP, París 2024.

El surrealismo llegó a la pintora, escultora y poeta estadounidense Dorothea Tanning cuando la Segunda Guerra Mundial obligó a muchos artistas a abandonar Europa. Después de estudiar arte en Chicago, Tanning trabajó como ilustradora independiente y luego se mudó a Nueva York, donde vio la histórica exposición de 1936 “Arte fantástico, dadaísmo, surrealismo” en el MoMA. “Pensé, ¡Dios mío! Puedo seguir adelante y hacer lo que siempre he hecho”, recordó más tarde. Unos años más tarde conoció al marchante de arte Julien Levy y, a través de él, a los surrealistas que habían huido de la Francia ocupada por los nazis. Uno de ellos fue Max Ernst, quien visitó su estudio en 1942 para ayudar a su esposa, Peggy Guggenheim, a seleccionar obras para su exposición “31 mujeres”.

La pintura en el caballete de Tanning durante esa visita fue Cumpleaños (1942), un autorretrato de un Tanning semidesnudo abriendo una puerta que deja al descubierto un pasillo interminable de puertas semiabiertas; Finalmente fue elegido para participar en la exposición del Guggenheim. Tanning y Ernst comenzaron una relación y estuvieron juntos durante 34 años, casándose en una ceremonia doble con Man Ray y Juliet Browner en 1946, después del divorcio de Ernst del Guggenheim a principios de ese año.

Tanning siguió interesada en lo ilógico y lo imposible a lo largo de su carrera, pintando temas surrealistas como la femme-enfant (mujer-niño) y el juego de ajedrez. Endgame (1944) muestra un zapato de satén blanco pisoteando a un obispo sobre un tablero a cuadros, con una escena trompe l'oeil de Arizona (donde ella y Ernst pasaban los veranos) en la parte inferior. "Todo lo que es ordinario y frecuente no me interesa, así que tengo que tomar una dirección solitaria y arriesgada", dijo Tanning una vez a un entrevistador. "Si te parece enigmático, bueno, supongo que eso es lo que quería que hiciera".

Rita Kernn-Larsen

Rita Kernn-Larsen en Copenhague, 1934

Foto: De la colección de su hija Danielle Grünberg. Archivos de Rita Kernn-Larsen, cortesía de Christy Wolfe.

Rita Kernn-Larsen, una de las pocas mujeres activas en el movimiento surrealista internacional durante su apogeo, nació en Dinamarca y formó parte del círculo surrealista danés en la década de 1930. Expuso sus pinturas, saturadas de recuerdos, objetos imaginarios y partes de sueños, con los surrealistas en 1935 en Copenhague, Oslo, la ciudad sueca de Lund y Londres, y en la Exposición Internacional Surrealista de 1938 en París.

Peggy Guggenheim conoció a Kernn-Larsen en París y le ofreció una exposición individual en su galería Guggenheim Jeune de Londres en 1938. Entre las 36 pinturas de la exposición se encontraba Know Thyself (1937), un autorretrato teñido de rojo en el que la artista explora el tema femme-arbre (mujer-árbol) como un tallo del que brotan ramas con hojas que parecen labios de mujer. Kernn-Larsen hizo sus propios marcos para muchas de las pinturas de la exposición, como uno con una estaca de madera extendida clavada en una maceta.

El estallido de la Segunda Guerra Mundial poco después de su exposición individual obligó a la artista a permanecer en Londres, donde conoció a los surrealistas británicos y participó en otras exposiciones surrealistas. Después de la guerra se volvió cada vez más hacia la abstracción, creando obras basadas en la naturaleza y experimentando con la cerámica y el collage.

Ithell Colquhoun

Ithell Colquhoun, 1949.

Foto: Reg Speller/Fox Photos/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

Ithell Colquhoun fue un ocultista que tuvo una breve aventura con los surrealistas británicos en la década de 1930, adoptando con entusiasmo su técnica del automatismo antes de cortar formalmente los lazos con ellos en 1940. Viviendo principalmente en el Reino Unido, Colquhoun conoció a los surrealistas mientras estuvo brevemente en París en principios de la década de 1930. De regreso a Londres, fue a ver la Exposición Surrealista Internacional de 1936 en las New Burlington Galleries y asistió a una conferencia relacionada de Salvador Dalí (donde, notoriamente, casi se asfixió mientras llevaba un traje de buceo).

Se interesó en lo que Dalí llamó su método paranoico-crítico de pintar escenas muy realistas imbuidas de ambigüedad, y pronto comenzó a exagerar las cualidades humanas de sus obras botánicas. Su pintura Scylla (1938) podría verse como formaciones rocosas en un cuerpo de agua, o alternativamente como un autorretrato de las propias piernas y la parte inferior del torso de Colquhoun en un baño con rocas en lugar de sus muslos y algas como su triángulo púbico. El título hace referencia a un monstruo mítico griego que vivía en un estrecho canal de agua y se alimentaba de los marineros que pasaban por allí.

ColquhounTuvo una exposición conjunta con Roland Penrose en la Mayor Gallery de Londres en 1939, mostrando 14 pinturas al óleo y dos objetos tallados, pero al año siguiente puso fin a su asociación formal con los surrealistas británicos para tener más tiempo para dedicarse a su interés por el ocultismo. Colquhoun continuó usando la técnica del automatismo y dijo que se sintió surrealista por el resto de su vida.

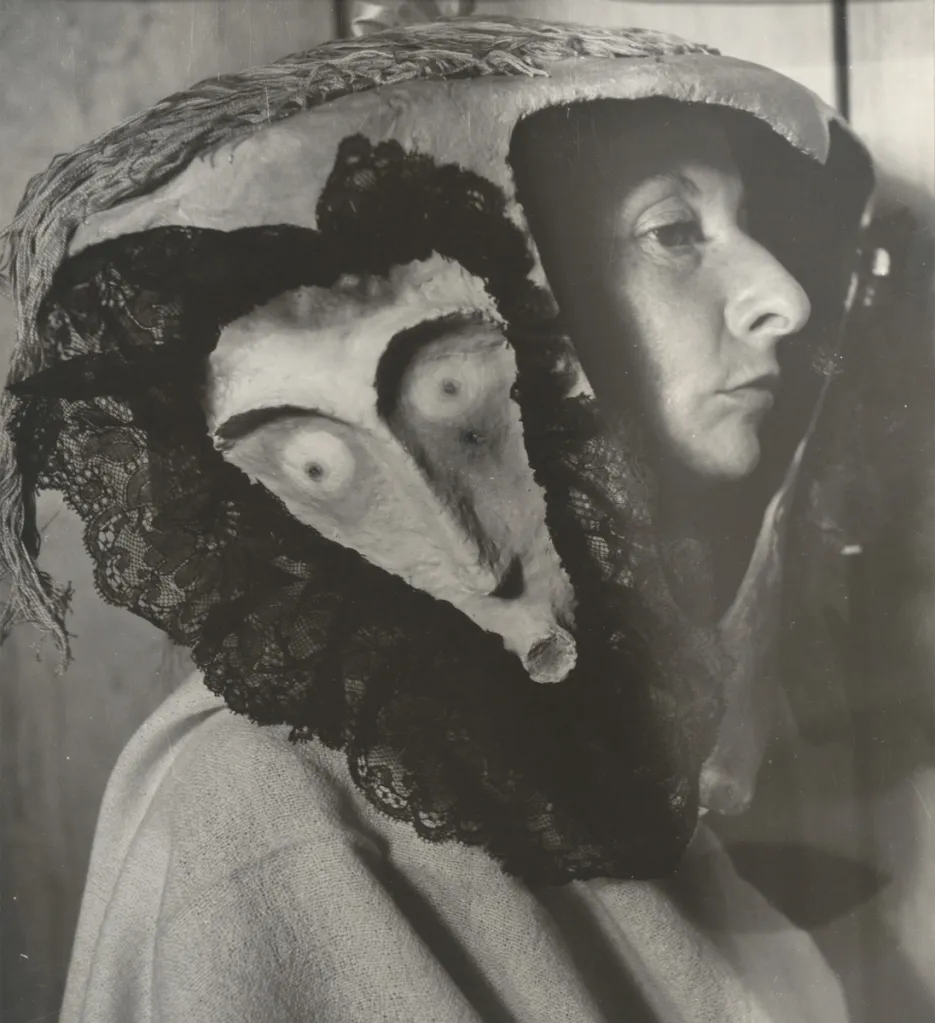

Remedios Varo

Kati Horna, (Remedios Varo con máscara de Leonora Carrington), 1962

Kati Horna, Sin título (Remedios Varo con máscara de Leonora Carrington), 1962

Foto: Colección del Museo de Arte Moderno de Nueva York. Copyright de la imagen digital © The Museum of Modern Art/Con licencia de SCALA/Art Resource, Nueva York. Copyright de la obra © Ana María Norah Horna y Fernández, todos los derechos reservados.

En pinturas íntimas e imaginativas que retratan una realidad alternativa con la minuciosa exactitud de un miniaturista, Remedios Varo, nacida en España, creó un reino idiosincrásico. En el mundo de Varo, los animales, las plantas, los humanos y los objetos mecánicos estaban todos interconectados. Cada figura tenía los rasgos físicos característicos del artista: un rostro en forma de corazón, nariz larga, cabello espeso y grandes ojos almendrados. Y transfirió sus imágenes de una superficie a otra utilizando la técnica decorativa de la calcomanía adoptada por los surrealistas, en la que se esparce tinta o pintura sobre una superficie y luego se presiona con papel de aluminio o papel para crear patrones.

Varo pasó a formar parte del círculo surrealista después de que se mudó de España a París en 1937 y comenzó a exponer con ellos. Si bien ella y los surrealistas compartían el interés de conectar los mundos animal, vegetal y mineral, ella planificó cuidadosamente sus pinturas en lugar de confiar en el automatismo o dejar las cosas al azar. “A veces participé con obras en sus exposiciones; Mi posición era la de un oyente tímido y humilde”, dijo Varo en una entrevista de 1957 sobre su tiempo con los surrealistas en París. “Estaba junto a ellos porque sentía cierta afinidad. Hoy no pertenezco a ningún grupo; Pinto lo que se me ocurre y eso es todo”.

Varo huyó de Francia en 1941 antes de la invasión nazi y se mudó a México, donde se hizo amiga de Leonora Carrington y otros refugiados surrealistas europeos. Fue allí también donde formó una relación íntima con el exiliado político Walter Gruen, cuyo apoyo emocional y financiero le permitió dedicarse a su arte a tiempo completo. Sus obras más ambiciosas las creó entre su matrimonio con Gruen en 1953 y su muerte, a los 54 años, en 1963.

kay sabio

Lee Miller, Woodbury, Connecticut, EE. UU. 1946

Foto: Copyright © Lee Miller Archives 2024. Todos los derechos reservados.

La artista nacida en Estados Unidos Kay Sage utilizó paisajes como metáforas visuales de estados mentales y espirituales, en panoramas de tonos neutros que recuerdan a Giorgio de Chirico. Conocida principalmente como pintora, aunque también fue una poeta publicada, Sage pasó los inicios de su carrera en Italia y Francia. Sus paisajes suelen ser desnudos y representan espacios inspirados más en la imaginación que en la naturaleza, poblados de edificios inacabados. En Tomorrow Is Never (1955), imponentes andamios emergen de nubes nebulosas y rodean estructuras drapeadas imperceptibles.

Después de estudiar arte en Washington, D.C. y Roma, Sage se mudó a París en 1937, donde conoció a varios artistas del círculo surrealista. Cuando estalló la Segunda Guerra Mundial, se mudó a Nueva York con su socio, el pintor surrealista Yves Tanguy, y ayudó a conseguir pasajes a los Estados Unidos para Breton y otros. Ella y Tanguy finalmente se casaron en Las Vegas y se establecieron en Woodbury, Connecticut, donde tuvo sus años más productivos, exhibiendo su trabajo y organizando exposiciones para surrealistas franceses.

Lee Miller

Eileen Agar, Lee Miller en el Hotel Vaste Horizon, Mougins, Francia, septiembre de 1937

Foto: Colección de la Tate, Londres. Copyright de la imagen digital © Tate, Londres/Art Resource, Nueva York. Copyright de la obra de arte © Estate of Eileen Agar. Todos los derechos reservados 2024/Servicio de Copyright Bridgeman.

La fotógrafa estadounidense Lee Miller comenzó su carrera frente a la cámara como modelo de Vogue. Al cabo de una década, hizo su primer autorretrato (publicado en la edición de septiembre de 1930 de Vogue), que presagió las formas en que esta creativa fotógrafa llevaría su ojo para lo inesperado al encuadre en blanco y negro. Uno de los fotógrafos para los que posó en Vogue fue Edward Steichen, quien le sugirió estudiar con Man Ray.

Miller se mudó a París en 1929, donde fue alumna y asistente de estudio de Man Ray (además de amante y musa), y parte de un círculo modernista de artistas. Juntos, ella y Man Ray inventaron la técnica de “solarización” mediante la cual se invierten el blanco y el negro; fue descubierta, dijo Miller, cuando accidentalmente encendió las luces mientras revelaba una fotografía. Miller también modeló para el fotógrafo surrealista, en cierto modo: es su ojo el que flota en la punta del péndulo del metrónomo en Objeto indestructible de Ray (1923). Durante su tiempo con Man Ray, continuó tomando fotografías; Después de dejar Man Ray en 1932, Miller regresó a Nueva York para abrir su propio estudio.

En 1934, Miller se casó con Aziz Eloui Bey y se mudó con él a El Cairo, mientras realizaba viajes en solitario a París. En uno de estos viajes conoció al artista Roland Penrose; se mudó a Londres en 1939, en parte para entablar una relación con él. Como acababa de estallar la Segunda Guerra Mundial y Vogue británica perdió miembros de su personal en el esfuerzo bélico, Miller fue contratada como fotógrafa y aportó su experiencia e imaginación surrealistas a sus tareas editoriales. Para un artículo que ilustra ejercicios, por ejemplo, utilizó exposiciones dobles y triples para mostrar el arco del movimiento en una sola imagen. Para un artículo llamado “Hats Follow Suit” a finales de 1942, convirtió fotografías de rostros en naipes con la ayuda del departamento de arte de la revista, posiblemente inspirada por la idea de Man Ray de crear una baraja de cartas surrealista. También eligió escenarios inusuales para la fotografía de moda, como los edificios europeos destruidos por los bombardeos aéreos o los esqueletos de dinosaurios en el Museo de Historia Natural de Nueva York.

Alicia Rahon

Walter Reuter, Alice Paalen en México, c. 1942

Foto: Imagen digital cortesía de Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco.

Igualmente inspirada por las pinturas rupestres prehistóricas y el surrealismo, la pintora francesa Alice Rahon (nacida Alice Phillipot) abordó la mitología, la magia y la memoria en sus lienzos texturizados. Conocida principalmente por su poesía cuando se movía en los círculos artísticos del París de los años 1920, Rahon, junto con su marido en ese momento, el artista Wolfgang Paalen, pasó a formar parte del conjunto surrealista de Breton y estuvo activa con el grupo durante los años 1930.

Rahon conoció a Frida Kahlo cuando esta última llegó a París en 1939, y Kahlo la invitó a ella, a Paalen y a su amiga la fotógrafa Eva Sulzer a visitarla en la Ciudad de México. Con el estallido de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, los Paalen decidieron quedarse permanentemente en México, y fue allí donde Rahon comenzó a pintar. Se unió al círculo surrealista local que incluía a Carrington y Varo, y tras publicar su último libro de poesía en 1941 se dedicó por completo a la pintura. En 1946 se convirtió en ciudadana mexicana y en 1947 se divorció de Paalen y se rebautizó como Alice Rahon.

El estilo de Rahon era figurativo y utilizó materiales extraños como alambre de hierro, cuerdas, roca volcánica, arena, crayones, gouache, tinta y encontró objetos como alas y plumas de mariposa. Creaba texturas similares a papel de lija en las superficies de sus lienzos y luego las grababa utilizando una técnica de esgrafiado, exponiendo las capas subyacentes. Tuvo una exposición individual en el Museo de Arte Moderno de San Francisco en 1945 y también mostró su trabajo en la galería Art of This Century de Peggy Guggenheim. “Lo Invisible nos habla y el mundo que pinta toma la forma de apariciones”, comentó una vez. “Despierta en cada uno de nosotros ese anhelo por lo maravilloso y nos muestra el camino de regreso a ello”.

Valentin Hugo

Man Ray, Valentín Hugo, c. 1930

Foto: Colección del Museo Nacional de Arte Moderno, Centro Georges Pompidou, París. Imagen digital Telimage, París. Copyright de la obra de arte © Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), Nueva York/ADAGP, París 2024.

Una mano con un guante marrón mete inquietantemente un dedo bajo el borde de un guante blanco que sostiene un dado en Object (1931), un montaje que Valentine Hugo hizo en la época en que trabajaba en la Oficina Parisina de Investigación Surrealista. Aquí fue donde comenzó a hacer objetos surrealistas, aunque ya llevaba años trabajando como artista, principalmente creando ilustraciones de moda y diseñando máscaras y trajes para los Ballets Russe, producciones teatrales y bailes de disfraces.

Hugo mostró Objeto en la Exposición Surréaliste de 1933 en París y también participó en la exposición “Arte fantástico, dadaísmo, surrealismo” de 1936 en el MoMA, exhibiendo algunas pinturas al óleo (incluidos retratos que pintó de memoria de los poetas surrealistas Eluard, Breton, Tristan Tzara). , René Crevel, Benjamin Péret y René Char). Trabajando con pinturas-collage, grabados a punta seca y litografías, ilustró varios textos surrealistas entre 1933 y 1937. Como parte del círculo íntimo surrealista, también jugó el popular juego surrealista cadáver exquisito con Breton y otros como Eluard, Tzara y Greta. Knutson, y algunos de los dibujos resultantes se exhibieron como obras de arte independientes en la exposición del MoMA de 1936.

En la década de 1940, sin embargo, Hugo dejó atrás a los surrealistas y volvió a las ilustraciones de libros y a los diseños de vestuario y escenografía para teatro.

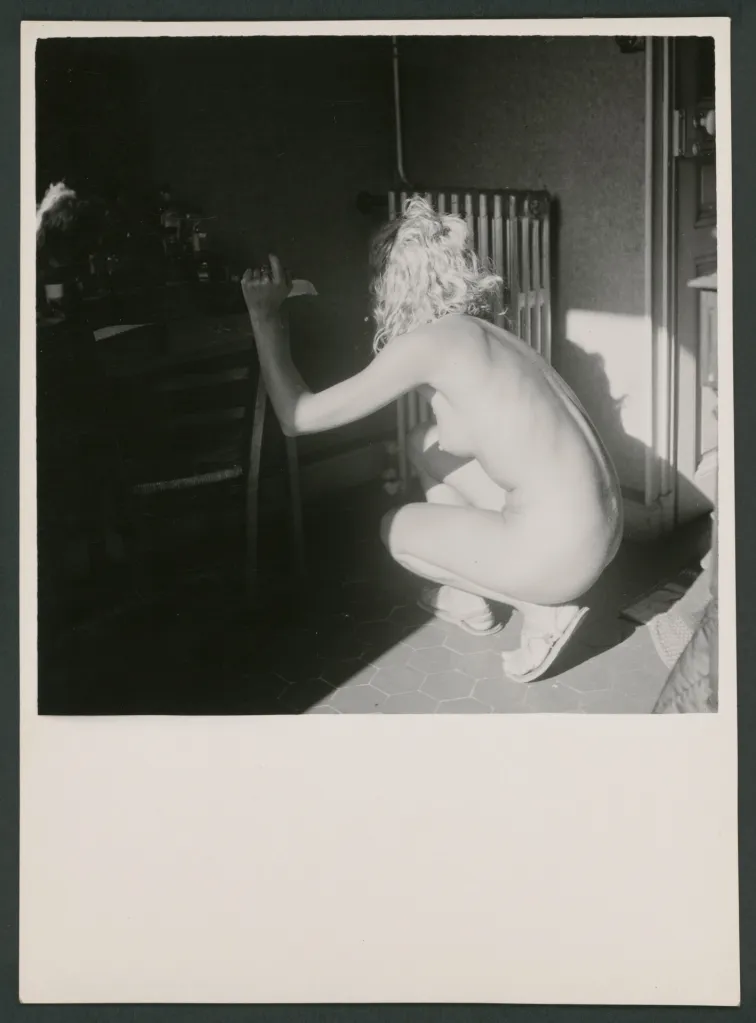

Jacqueline Lamba

Dora Maar, Jacqueline Lamba desnuda, en verano, 1936

Foto: Colección del Museo Nacional Picasso, París. Copyright de la imagen digital © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, Nueva York. policía de obras de arteyright © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), Nueva York/ADAGP, París.

Si el surrealismo tendía a reducir a las mujeres a musas atractivas, entonces nadie pagó el precio tanto como la talentosa y sorprendentemente bella Jacqueline Lamba. Incluso ella sabía que era demasiado atractiva para su propio bien. “Si hubiera sido menos hermosa”, le dijo a la historiadora de arte Martica Sawin cuando tenía 70 años, “habría sido mejor pintora”.

Lamba, nacido en Francia, no siempre fue pintor; Después de asistir a la Ecole de l'Union Centrale des Arts Decoratifs de 1926 a 1929, comenzó su carrera diseñando libros, publicidad, textiles y papel para grandes minoristas. Sólo entonces empezó a pintar.

Lamba comenzó a leer los escritos de Breton en 1934 y encontró la manera de encontrarlo "accidentalmente" en un café ese año; se casaron menos de tres meses después. (Eluard y Alberto Giacometti fueron sus testigos, no había familiares presentes y las fotos fueron tomadas por Man Ray, quien fotografió a Lamba desnuda con Eluard y Giacometti como un guiño a Déjeuner sur l'Herbe de Manet). Su relación fue difícil desde el principio. y Lamba sintió que Breton minimizó su necesidad de pintar. Sin embargo, fue incluida en las calcomanías surrealistas y en los exquisitos juegos de cadáveres, y expuso con el grupo en 1935 y en 1936, cuando dos de sus objetos y el cuadro Les Heures (1935), un lienzo ovalado con una caracola antropomorfa sola en un fondo oscuro, cuerpo de agua—se mostraron en la Exposición Internacional Surrealista de Londres. Lamba también expuso en la Exposición Internacional Surrealista de 1938 en París y en la primera muestra surrealista de posguerra, “La Surréalisme en 1947”, en la Galerie Maeght de París, pero para entonces había perdido interés en el movimiento.

Lamba es menos conocida que otras mujeres surrealistas, en parte porque su condición de esposa de Breton a menudo eclipsaba su trabajo; además, queda poco de sus primeros trabajos. Todo lo que almacenó en su apartamento de la Rue Fontaine en París cuando ella y Breton huyeron durante la guerra ya no estaba cuando regresó en 1954. Ella misma también destruyó muchas de sus obras surrealistas.

Elsa Schiaparelli

Man Ray, Elsa Schiaparelli, 1933

Foto: Imagen digital Telimage, París. Copyright de la obra de arte © Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), Nueva York/ADAGP, París 2024.

La moda era el lugar donde los surrealistas podían hacer que el cuerpo fuera absurdo en el mundo real, y la modista italiana Elsa Schiaparelli lo hizo mejor. Conocida familiarmente como Schiap, la diseñadora hacía cosas divertidas y extrañas con la ropa: añadió garras a las puntas de los dedos de los guantes y manos a los cinturones, entre otras intervenciones. También colaboró con muchos surrealistas, a quienes conoció a través de su amiga Gaby Picabia, esposa del pintor francés de vanguardia Francis Picabia.

Una de sus primeras colaboraciones artísticas fue en 1936 con Dalí, quien le mostró un dibujo de una mujer vestida con un traje que tenía cajones donde debería haber bolsillos. Schiaparelli tomó esa idea e hizo una serie de trajes y abrigos de terciopelo azul marino que parecían tener cajones, con perillas de plástico negro, como parte de su colección de alta costura de invierno de 1936-1937. Ese mismo año, Meret Oppenheim diseñó un brazalete cubierto de piel para Schiaparelli (un precursor de la taza de té forrada de piel más famosa de Oppenheim), y en 1937 Leonor Fini diseñó una botella con forma de torso para un perfume de Schiaparelli llamado Shocking (supuestamente usando el perfume de Mae West). cuerpo como inspiración).

Los diseños de Schiaparelli eran extraños pero también muy ponibles, un equilibrio difícil de lograr. Su Shoe Hat (1937), un tocado que parecía un zapato de tacón alto al revés, estaba hecho de fieltro y terciopelo y era fácil de usar. El vestido esqueleto (1938) que diseñó en colaboración con Dalí tenía costillas, columna y pelvis elevadas distintivas, hechas de un acolchado trapunto colocado sobre una funda de crepé que llegaba hasta el suelo.

Claude Cahun

Claude Cahun, Sin título, 1921-22

Foto: Colección del Museo de Arte Moderno de Nueva York. Copyright de la imagen digital © The Museum of Modern Art/Con licencia de SCALA/Art Resource, Nueva York. Copyright de la obra de arte © Estate de Claude Cahun.

Las realidades posibles son infinitas en las fotografías, fotomontajes, performances y escritos de Claude Cahun (de soltera Lucy Schwob), nacida en Francia. Activa principalmente en París en las décadas de 1920 y 1930, realizó retratos fotográficos y autorretratos que a menudo incluían imágenes divididas y duplicadas, espejos y ambigüedad de género. (Ella misma, como su seudónimo implica, tenía un género fluido.) Cahun también hizo lo que ella llamó “pinturas” fotográficas: mundos en miniatura o naturalezas muertas hechas a partir de objetos ensamblados y luego fotografiados.

Cahun se asoció con los surrealistas en la década de 1930 y firmó muchas de sus declaraciones colectivas, pero nunca fue miembro formalmente. Participó en algunas exposiciones surrealistas, incluida la "Exposición Surréaliste d'Objets" en 1936. Para esa exposición, escribió un ensayo titulado "Cuidado con los objetos domésticos" que decía: "Tú"Deberías descubrir, manipular, domesticar y fabricar objetos irracionales por ti mismo". También contribuyó con una pelota de tenis pintada para que pareciera un globo ocular y cubierta de pelo rizado.

Ella y su compañera de toda la vida Suzanne Malherbe, que usó el nombre de Marcel Moore profesionalmente, colaboraron a menudo, incluso en los fotomontajes utilizados para ilustrar el libro de sueños y poemas autobiográficos de Cahun de 1930, Aveux non Avenus. En 1939, la pareja se mudó de París a Jersey, una de las Islas del Canal, para escapar de la persecución como judíos. Allí realizaron fotomontajes políticos y participaron activamente en la Resistencia francesa, lo que llevó a su arresto y encarcelamiento en 1944 hasta el final de la guerra.

15 Important Women Surrealists

BY KAREN CHERNICK

The founding French Surrealists loved the subconscious. They also loved women—as muses, as subjects of erotic desire, as sources of inspiration, but not necessarily as artists at first. Women weren’t present at the birth of the movement when poet André Breton published his Surrealist Manifesto in 1924. But inevitably women were attracted to the movement and its revolutionary ideas—interpreting dreams as expressions of subconscious thought, fusing the familiar with the unknown, and generally doing away with rational inhibition. Some of them came to Surrealism through contact with male Surrealists, some came on their own, and others, outside Paris, came to it as international exhibitions widened the Surrealist circle.

And so just a few years after Breton defined Surrealism, staking his claim in conceptual ground that it was “psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express—verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner—the actual functioning of thought,” women actively participated. They showed their paintings, photographs, collages, assemblages, garments, and sculptures in group Surrealist exhibitions and had their own solo shows, with catalog introductions written by Surrealists in their circle.

Between 1924, when Breton released the first Surrealist Manifesto, and 1947, when a major exhibition at Galerie Maeght celebrated the postwar return of Surrealism to Paris, the “first generation” of Surrealists included numerous women, many more than the 15 included here. Each had her own complex relationship with the movement.

“The diversity of experience and attitude on the part of women artists active in Surrealism has proved both an obstacle and a challenge,” wrote art historian Whitney Chadwick in her groundbreaking 1985 text Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement. “In the end, I came to view such diversity as a tribute to these women, an affirmation of their strength as individuals and a mark of their commitment to a form of creative expression in which personal reality dominates.”

Some of the artists profiled below proudly carried the label, and others emphatically denied being Surrealists. But in a sense, isn’t it a Surrealist trait par excellence to defy being squeezed neatly into a box?

Meret Oppenheim

Man Ray, <em>Meret Oppenheim</em>, 1932

Man Ray, Meret Oppenheim, 1932

Photo : Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Digital Image copyright © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris 2024.

Meret Oppenheim took useful things, often items used by women, and with simple interventions rendered them utterly bizarre. She set a gold ring with a sparkly white sugar cube instead of a jewel; in My Nurse (1936–37) she trussed two high-heeled shoes and set them on a metal platter like roasted poultry; and, most famously, she lined a teacup, saucer, and spoon in fur in her Object (1936), now one of the best known Surrealist sculptures. “The ‘fur-lined tea set’ makes concretely real the most extreme, the most bizarre improbability,” said museum director Alfred H. Barr when Object was shown in “Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism,” a major 1936–37 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Oppenheim’s sculpture demonstrated the Surrealist habit of defying reason and allowing unconscious and unexpected connections to emerge. The Swiss artist entered the Surrealist circle after moving from Basel to Paris in 1932, becoming a muse to Man Ray. By 1936 she had her first solo show, in Basel, for which Max Ernst (briefly her romantic partner) wrote the introductory essay. Her work spanned assemblages, paintings, and design pieces (including furniture and accessories, some in collaboration with Elsa Schiaparelli). Still, she didn’t like being pigeonholed. “I never collaborated with the Surrealists. I always did what I wanted and was discovered by them by chance, you might say,” Oppenheim stated in a 1981 interview.

When World War II broke out, Oppenheim felt that her objects were too whimsical and shifted to painting, but she often destroyed or reworked her increasingly abstract canvases. By the late 1950s she had decided to end her affiliation with the Surrealists, and her final Surrealist work was Spring Banquet (1959), a feast served on a nude woman’s body, utensils forbidden, which she first created for a party in Bern and then staged, at Breton’s request, at the 1959 Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme in Paris.

Dora Maar

Dora Maar, <em>Self-Portrait</em>, c. 1930

Dora Maar, Self-Portrait, c. 1930

Photo : Collection of the Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. Digital Image copyright © CNAC/MNAM, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

Dora Maar never identified the intriguingly hideous creature appearing in one of her best-known photographs, Père Ubu (1936), which epitomizes her fusion of strangeness and beauty; some have guessed that it is an armadillo fetus. Of the six Surrealist exhibitions Maar participated in during the 1930s, Père Ubu was shown in three (including the 1936 London International Surrealist Exhibition).

Maar worked as a commercial photographer but also moved in Surrealist circles. She and Jacqueline Lamba studied together at the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, and Maar befriended fellow photographer Man Ray around the time that he was working with Lee Miller (who also became a close friend). In her studio, Maar photographed Meret Oppenheim and Frida Kahlo. And she famously was Picasso’s lover and muse for nearly a decade.

At the photography studio that Maar opened in 1931 with Pierre Kéfer, she was commissioned by designers such as Coco Chanel, Elsa Schiaparelli, and Jeanne Lanvin to create commercial photographs with an experimental touch. She brought techniques such as double exposure, photomontage, and collage to her commercial work, blurring reality and artifice and combining objects in unexpected ways. In The Years Lie in Wait for You (1935), a spiderweb is superimposed over the image of a woman’s face in a shot likely created as an advertisement for an antiaging cream.

Eileen Agar

Eileen Agar, <em>Self-Portrait</em>, n.d.

Eileen Agar, Self-Portrait, n.d.

Photo : Private Collection. Digital image copyright © Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images. Artwork copyright © Estate of Eileen Agar. All rights reserved 2024/Bridgeman Images.

Collage was an important part of the practice of Argentine-British artist Eileen Agar. She filled her studio with what she called “fantastic bric-a-brac”—including textiles, fossils, bones, shells, leaves, and many other things she collected—and used this material to create chance combinations of curious objects. Among these is Angel of Anarchy (1936–40), for which she used a plaster head as a blank canvas and adorned it with fur, ostrich feathers, fabrics, seashells, and gemstones. Still, she was a somewhat reluctant Surrealist, unwilling to deny her love of Cubism and abstraction in order to fit in.

She first encountered the Surrealists when she briefly moved to Paris in 1929, where she befriended Breton and the French Surrealist poet Paul Eluard, with whom she would later have an affair. When Agar returned to England, she met the Surrealist painter Paul Nash, embarking on an intense artistic and romantic liaison with him (despite an ongoing relationship with the Hungarian writer Joseph Bard that would span 50 years).

Encouraged by Nash, Roland Penrose and Herbert Read visited her studio while curating the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London, selecting three oil paintings and five objects. “The sudden attention took me by surprise,” Agar recalled of the visit. “One day I was an artist exploring highly personal combinations of form and content, and the next I was calmly informed I was a Surrealist!” She rejected the label but showed with them anyway, allowing Angel of Anarchy to be included in Surrealist exhibitions in London and Amsterdam.

Leonor Fini

Dora Maar, <em>Portrait of Leonor Fini Seated</em>, c. 1934

Dora Maar, Portrait of Leonor Fini Seated, c. 1934

Photo : Collection of the Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. Digital Image copyright © CNAC/MNAM, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

Leonor Fini was all about metamorphosis, fluidity, and ambiguity, drawn to sphinxes and other human/animal hybrids. In The Shepherdess of the Sphinxes (1941), Fini painted nonsensical creatures that were half-woman, half-lion being shepherded by an oversize Amazon with a full mane of hair—an uncanny combination of realism and pure fantasy.

The self-taught Argentine-Italian painter famously used her own body as a laboratory of creative expression, dressing up in fantastical ways and wearing intentionally ripped clothes or masks. (Her friends Dora Maar and Lee Miller photographed her in these outfits for posterity.) She didn’t particularly want to become a card-carrying Surrealist, even though her approach resonated with the Surrealists’ interest in discovering hidden correspondences between things.

It was Breton who turned her off Surrealism. “I hated his anti-homosexual attitudes and also his misogyny,” the openly bisexual Fini said in a 1994 interview. “It seemed that women were expected to keep quiet, yet I felt that I was just as good as the men.” Still, she met many Surrealists after moving from Italy to Paris in 1931 and participated in major Surrealist exhibitions. After her first solo show in 1932 at Galerie Bonjean (then directed by Christian Dior), she contributed work to “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism” at MoMA in 1936. In the same year, she also started showing with New York gallerist and Surrealist champion Julien Levy. Right before World War II erupted, Fini curated an exhibition of Surrealist furniturefor a Parisian gallery owned by her friend Leo Castelli, and Peggy Guggenheim included her in “31 Women”at her Art of This Century gallery in New York in 1943.

Dorothea Tanning

Man Ray, <em>Dorothea Tanning</em>, 1942

Man Ray, Dorothea Tanning, 1942

Photo : Digital image Telimage, Paris. Artwork copyright © Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris 2024.

Surrealism made its way to the American-born painter, sculptor, and poet Dorothea Tanning when World War II forced many artists to leave Europe. After studying art in Chicago, Tanning worked as a freelance illustrator and then moved to New York, where she saw the landmark 1936 “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism” exhibition at MoMA. “I thought, Gosh! I can go ahead and do what I’ve always been doing,” she later recalled. A few years later she met art dealer Julien Levy and, through him, Surrealists who had fled Nazi-occupied France. One of these was Max Ernst, who visited her studio in 1942 to help his wife, Peggy Guggenheim, select works for her “31 Women” exhibition.

The painting on Tanning’s easel during that visit was Birthday (1942), a self-portrait of a half-nude Tanning opening a door that exposes an endless hallway of semi-open doors; it was ultimately chosen to participate in Guggenheim’s exhibition. Tanning and Ernst started a relationship and were together for 34 years, marrying in a double ceremony with Man Ray and Juliet Browner in 1946 after Ernst’s divorce from Guggenheim earlier that year.

Tanning remained interested in the illogical and the impossible throughout her career, painting Surrealist themes such as the femme-enfant (woman-child) and the game of chess. Endgame (1944) shows a white satin shoe stomping a bishop on a checked board, with a trompe l’oeil scene of Arizona (where she and Ernst spent summers) at the bottom. “Anything that is ordinary and frequent is uninteresting to me, so I have to go in a solitary and risky direction,” Tanning once told an interviewer. “If it strikes you as being enigmatic, well, I suppose that’s what I wanted it to do.”

Rita Kernn-Larsen

Rita Kernn-Larsen in Copenhagen, 1934

Rita Kernn-Larsen in Copenhagen, 1934

Photo : From her daughter Danielle Grünberg’s collection. Rita Kernn-Larsen Archives, courtesy of Christy Wolfe.

One of the few women active in the international Surrealist movement during its heyday, Rita Kernn-Larsen was born in Denmark and was part of the Danish Surrealist circle in the 1930s. She exhibited her paintings—saturated with memories, imaginary objects, and parts of dreams—with the Surrealists in 1935 in Copenhagen, Oslo, the Swedish city of Lund, and London, and at the 1938 International Surrealist Exhibitionin Paris.

Peggy Guggenheim met Kernn-Larsen in Paris and gave her a solo show at her Guggenheim Jeune gallery in London in 1938. Among the 36 paintings in the exhibition was Know Thyself (1937), a red-tinted self-portrait in which the artist explores the femme-arbre (woman-tree) theme as a stem sprouts branches with leaves that look like women’s lips. Kernn-Larsen made her own frames for many of the paintings in the exhibition, such as one with an extended wooden stake that was stuck into a flowerpot.

The outbreak of World War II shortly after her solo show forced the artist to stay in London, where she got to know the British Surrealists and participated in other Surrealist exhibitions. After the war she turned increasingly toward abstraction, creating works based on nature and experimenting with ceramics and collage.

Ithell Colquhoun

Ithell Colquhoun, 1949.

Ithell Colquhoun, 1949.

Photo : Reg Speller/Fox Photos/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

Ithell Colquhoun was an occultist who had a brief fling with the British Surrealists in the 1930s, enthusiastically adopting their automatism technique before formally severing ties with them in 1940. Mostly living in the United Kingdom, Colquhoun became aware of the Surrealists while briefly in Paris in the early 1930s. Back in London, she went to see the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition at the New Burlington Galleries and attended a related lecture by Salvador Dalí (where, notoriously, he nearly suffocated while wearing a diving suit).

She became interested in what Dalí called his paranoiac-critical method of painting highly realistic scenes imbued with ambiguity, and she soon started exaggerating the human qualities of her botanical works. Her painting Scylla (1938) could be seen as rock formations in a body of water, or alternatively as a self-portrait of Colquhoun’s own legs and lower torso in a bath with rocks standing in for her thighs and seaweed as her pubic triangle. The title refers to a mythical Greek monster that lived in a narrow channel of water and fed on sailors passing through.

Colquhoun had a joint show with Roland Penrose at London’s Mayor Gallery in 1939, showing 14 oil paintings and two carved objects, but the following year she ended her formal association with the British Surrealists so she would have more time to pursue her interest in the occult. Colquhoun continued to use the automatism technique and said she felt like a Surrealist for the rest of her life.

Remedios Varo

Kati Horna, <em>Untitled</em> (Remedios Varo wearing a mask by Leonora Carrington), 1962

Kati Horna, Untitled (Remedios Varo wearing a mask by Leonora Carrington), 1962

Photo : Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Digital image copyright © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © Ana María Norah Horna y Fernández, all rights reserved.

In intimate and imaginative paintings that portray an alternate reality with the painstaking exactitude of a miniaturist, Spanish-born Remedios Varo created an idiosyncratic realm. In Varo’s world, animals, plants, humans, and mechanical objects were all interconnected. Every figure had the artist’s signature physical features—a heart-shaped face, long nose, thick hair, and big almond-shaped eyes. And she transferred her images from one surface to another using the decalcomania decorative technique adopted by the Surrealists, wherein ink or paint is spread on a surface and then pressed with aluminum foil or paper to create patterns.

Varo became part of the Surrealist circle after she moved from Spain to Paris in 1937 and began exhibiting with them. While she and the Surrealists shared an interest in connecting the animal, vegetable, and mineral worlds, she carefully planned her paintings rather than relying on automatism or leaving things to chance. “Sometimes I participated with works in their exhibitions; my position was one of a timid and humble listener,” Varo said in a 1957 interview about her time with the Surrealists in Paris. “I was together with them because I felt a certain affinity. Today I do not belong to any group; I paint what occurs to me and that is all.”

Varo fled France in 1941 before the Nazi invasion and moved to Mexico, where she befriended Leonora Carrington and other European Surrealist refugees. It was there, too, that she formed an intimate relationship with the political exile Walter Gruen, whose emotional and financial support allowed her to pursue her art full time. Her most ambitious works were created between her marriage to Gruen in 1953 and her death, at age 54, in 1963.

Kay Sage

Lee Miller, <em>Kay Sage, Woodbury, Connecticut, USA</em>, 1946

Lee Miller, Kay Sage, Woodbury, Connecticut, USA, 1946

Photo : Copyright © Lee Miller Archives 2024. All rights reserved.

American-born artist Kay Sage used landscapes as visual metaphors for states of mind and spirit, in neutral-toned panoramas reminiscent of Giorgio de Chirico. Known mostly as a painter, though she was also a published poet, Sage spent her early career in Italy and France. Her landscapes are usually bare and represent space that is inspired more by imagination than by nature, populated with unfinished buildings. In Tomorrow Is Never (1955), towering scaffolds emerge from nebulous clouds and surround indiscernible draped structures.

After studying art in Washington, D.C., and Rome, Sage moved to Paris in 1937, where she met several artists in the Surrealist circle. When World War II broke out she moved to New York with her partner, the Surrealist painter Yves Tanguy, and helped arrange passage to the United States for Breton and others. She and Tanguy ultimately married in Las Vegas and settled in Woodbury, Connecticut, where she had her most productive years, exhibiting her work and organizing exhibitions for French Surrealists.

Lee Miller

Eileen Agar, <em>Lee Miller at the Hotel Vaste Horizon, Mougins, France, September 1937</em>, 1937

Eileen Agar, Lee Miller at the Hotel Vaste Horizon, Mougins, France, September 1937, 1937

Photo : Collection of Tate, London. Digital image copyright © Tate, London/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © Estate of Eileen Agar. All rights reserved 2024/Bridgeman Copyright Service.

American-born photographer Lee Miller began her career in front of the camera as a Vogue model. Within a decade she took her first self-portrait (published in Vogue’s September 1930 issue), which foreshadowed the ways this inventive photographer would bring her eye for the unexpected to the black-and-white frame. One of the photographers she posed for at Vogue was Edward Steichen, who suggested she study with Man Ray.

Miller moved to Paris in 1929, where she was Man Ray’s student and studio assistant (as well as lover and muse), and part of a modernist circle of artists. Together she and Man Ray invented the “solarization” technique by which black and white are reversed—discovered, Miller said, when she accidentally turned the lights on while developing a photograph. Miller modeled for the Surrealist photographer too, in a way: It is her eye that floats at the tip of the metronome pendulum in Ray’s Indestructible Object (1923). During her time with Man Ray, she continued to take photographs; after leaving Man Ray in 1932, Miller returned to New York to open her own studio.

In 1934 Miller married Aziz Eloui Bey and moved with him to Cairo, all the while taking solo trips to Paris. On one of these trips she met atist Roland Penrose; she moved to London in 1939, in part to pursue a relationship with him. As World War II had just broken out and British Vogue lost staff members to the war effort, Miller was hired as a photographer and brought her Surrealist background and imagination to her editorial duties. For a feature illustrating exercises, for example, she used double and triple exposures to show the arc of the movement in a single image. For a feature called “Hats Follow Suit” in late 1942, she turned headshots into playing cards with the help of the magazine’s art department, possibly inspired by Man Ray’s idea to create a Surrealist deck of cards. She also chose unusual settings for fashion photography, such as European buildings wrecked by aerial bombardments or the dinosaur skeletons in New York’s Museum of Natural History.

Alice Rahon

Walter Reuter, <em>Alice Paalen in Mexico</em>, c. 1942

Walter Reuter, Alice Paalen in Mexico, c. 1942

Photo : Digital image courtesy Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco.

Equally inspired by prehistoric cave paintings and Surrealism, French-born painter Alice Rahon (born Alice Phillipot) addressed mythology, magic, and memory on her textured canvases. Known mostly for her poetry when she moved in artistic circles in 1920s Paris, Rahon—along with her husband at the time, artist Wolfgang Paalen—became became part of Breton’s Surrealist set and was active with the group throughout the 1930s.

Rahon met Frida Kahlo when the latter came to Paris in 1939, and Kahlo invited her, Paalen, and their friend photographer Eva Sulzer, to visit her in Mexico City. With the outbreak of World War II, the Paalens decided to stay in Mexico permanently, and it was there that Rahon started painting. She joined the local Surrealist circle that included Carrington and Varo, and after publishing her final book of poetry in 1941 she dedicated herself completely to painting. In 1946, she became a Mexican citizen, and in 1947 she divorced Paalen and renamed herself Alice Rahon.

Rahon’s style was figurative, and she used odd materials such as iron wire, string, volcanic rock, sand, crayons, gouache, ink, and found objects like butterfly wings and feathers. She would create sandpaper-like textures on her canvas surfaces and then etch on them using a sgraffito technique, exposing underlying layers. She had a solo exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1945 and also showed her work at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery. “The Invisible speaks to us, and the world it paints takes the form of apparitions,” she once commented. “It awakens in each of us that yearning for the marvelous and shows us the way back to it.”

Valentine Hugo

Man Ray, <em>Valentine Hugo</em>, c. 1930

Man Ray, Valentine Hugo, c. 1930

Photo : Collection of the Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. Digital image Telimage, Paris. Artwork copyright © Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris 2024.

A hand in a brown glove unnervingly pokes one finger under the edge of a white glove holding a die in Object (1931), an assemblage Valentine Hugo made around the time she was active at the Parisian Bureau of Surrealist Research. This was where she began making Surrealist objects, though she’d been a working artist for years already by that point, mostly creating fashion illustrations and designing masks and costumes for the Ballets Russe, theater productions, and costume balls.

Hugo showed Object at the 1933 Exposition Surréaliste in Paris and also participated in the 1936 “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism” show at MoMA, exhibiting a few oil paintings (including portraits that she painted from memory of Surrealist poets Eluard, Breton, Tristan Tzara, René Crevel, Benjamin Péret, and René Char). Working across collage-paintings, drypoint etchings, and lithographs, she illustrated several Surrealist texts between 1933 and 37. Part of the Surrealist inner circle, she also played the popular Surrealist game exquisite corpse with Breton and others such as Eluard, Tzara, and Greta Knutson—with some of the resulting drawings being exhibited as standalone artworks at the 1936 MoMA exhibition.

In the 1940s, however, Hugo left the Surrealists behind, returning to book illustrations and costume and set designs for theater.

Jacqueline Lamba

Dora Maar, <em>Nude Jacqueline Lamba, in Summer</em>, 1936

Dora Maar, Nude Jacqueline Lamba, in Summer, 1936

Photo : Collection of the Musée national Picasso, Paris. Digital image copyright © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

If Surrealism tended to reduce women to fine-looking muses, then nobody paid the price quite like talented and strikingly beautiful Jacqueline Lamba. Even she knew she was too attractive for her own good. “If I had been less beautiful,” she said to art historian Martica Sawin while in her 70s, “I would have been a better painter.”

The French-born Lamba wasn’t always a painter; after attending the Ecole de l’Union Centrale des Arts Decoratifs from 1926 to 1929, she began her career designing books, advertising, textiles, and paper for big retailers. It was only then that she began to paint.

Lamba started reading Breton’s writings in 1934 and found a way to “accidentally” meet him at a café that year; they married less than three months later. (Eluard and Alberto Giacometti were their witnesses, no family was present, and photos were taken by Man Ray, who photographed Lamba nude with Eluard and Giacometti as a nod to Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’Herbe.) Their relationship was difficult from the start, and Lamba felt that Breton minimized her need to paint. Nonetheless she was included in Surrealist decalcomanias and exquisite corpse games, and she exhibited with the group in 1935 and in 1936, when two of her objects and the painting Les Heures (1935)—an oval canvas with an anthropomorphic conch shell alone in a dark body of water—were shown in the International Surrealist Exhibition in London. Lamba also showed at the International Surrealist Exhibition of 1938 in Paris and in the first postwar Surrealist show, “La Surréalisme en 1947,” at Paris’s Galerie Maeght, but by then she’d lost interest in the movement.

Lamba is less well-known than other women Surrealists, partially because her standing as Breton’s wife often overshadowed her work; moreover, little of her early work remains. Everything she stored in their Rue Fontaine apartment in Paris when she and Breton fled during the war was gone by the time she returned in 1954. She also destroyed many of her Surrealist works herself.

Elsa Schiaparelli

Man Ray, <em>Elsa Schiaparelli</em>, 1933

Man Ray, Elsa Schiaparelli, 1933

Photo : Digital image Telimage, Paris. Artwork copyright © Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris 2024.

Fashion was where Surrealists could render the body nonsensical in the real world, and Italian-born couturier Elsa Schiaparelli did it best. Known familiarly as Schiap, the designer did playfully bizarre things with clothes—she added claws to the fingertips of gloves and hands to belts, among other interventions. She also collaborated with many Surrealists, whom she met through her friend Gaby Picabia, wife of the avant-garde French painter Francis Picabia.

One of the first of her artist collaborations was in 1936 with Dalí, who showed her a drawing of a woman wearing a suit that had drawers where there should have been pockets. Schiaparelli took that idea and made a series of navy-blue velvet suits and coats that looked like they had drawers, complete with black plastic knobs, as part of her winter 1936–37 haute couture collection. That same year, Meret Oppenheim designed a bangle bracelet covered in fur for Schiaparelli (a forerunner of Oppenheim’s more famous fur-lined teacup), and in 1937 Leonor Fini designed a torso-shaped bottle for a Schiaparelli perfume called Shocking (allegedly using Mae West’s body as inspiration).

Schiaparelli’s designs were strange but also highly wearable, a difficult balance to achieve. Her Shoe Hat (1937), a headpiece that looked like an upside-down high-heeled shoe, was made of felt and velvet and easy to wear. The Skeleton Dress (1938) that she designed in collaboration with Dalí had distinctive raised ribs, spine, and pelvis, made from trapunto quilting laid atop a floor-length crepe sheath.

Claude Cahun

Claude Cahun, <em>Untitled</em>, 1921-22

Claude Cahun, Untitled, 1921-22

Photo : Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Digital image copyright © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © Estate of Claude Cahun.

Possible realities are endless in the photographs, photomontages, performances, and writings of French-born Claude Cahun (née Lucy Schwob). Active mostly in Paris in the 1920s and ’30s, she made photographic portraits and self-portraits that often included split and doubled images, mirrors, and gender ambiguity. (She herself, as her pseudonym implies, was gender-fluid.) Cahun also made what she called photographic “paintings”—miniature worlds or still lifes made from assembled objects, then photographed.

Cahun became associated with the Surrealists in the 1930s and signed many of their collective declarations, but she was never formally a member. She did participate in a few Surrealist exhibitions, including “Exposition Surréaliste d’Objets” in 1936. For that show she wrote an essay titled “Beware of Domestic Objects” that instructed, “You should discover, handle, tame, make irrational objects yourself.” She also contributed a tennis ball painted to look like an eyeball and covered with curly hair.

She and her lifelong partner Suzanne Malherbe, who used the name Marcel Moore professionally, collaborated often, including on the photomontages used to illustrate Cahun’s 1930 book of autobiographical poems and dreams, Aveux non Avenus. In 1939 the couple moved from Paris to Jersey, one of the Channel Islands, to escape persecution as Jews. There they made political photomontages and were active in the French Resistance, which led to their 1944 arrest and imprisonment until the end of the war.